บทความนี้ยังไม่มีฉบับภาษาไทยนะครับ :(

When it comes to string concatenation in Python, the + operator is probably your go-to method. It’s intuitive and easy to use. Perhaps, it feels that way because that’s how it’s taught in many Python introductory courses. However, those who have been using Python for quite a while would have probably seen a string method called join(), and it’s said to be faster than the + operator. You may have noticed the difference if you have tried both methods yourself. But why is this the case?

An article by Christopher Tao has already touched on this topic (and also inspired me to write this one!). His article is easy to digest; however, I find the explanation to be only partial. This article intends to dig a little deeper into the details of how Python is handling two different methods of concatenation, see how they perform, and analyze the results.

So, grab yourself a cup of coffee and get your Python interpreter ready to follow along!

The contents in this article apply to CPython implementation only.

Is It That Bad?

The + operator works just fine. So too with join(). They both can do the same job. Well, except that join() has a nice feature that allows you to add a separator in-between each string. Other than that, though, they both get you the same thing. It might not be worth the hassle to switch to something you are not familiar with if the impact is not too severe. Spoiler alert! There’s a pretty big difference in terms of performance.

It’s hard to convince someone without showing the results first, so let’s start by seeing how the two methods compare using the following snippet of code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

from timeit import timeit

num = int(1e6)

str_to_concat = "Hello!"

plus_time = timeit("c += str_to_concat",

setup="c=''",

number=num,

globals=globals())

join_time = timeit("''.join([str_to_concat] * num)",

number=1,

setup="c=''",

globals=globals()) +\

timeit("a=1", number=num)

Here’s what the code does:

- Line 1: Imports a function called

timeitfrom the moduletimeit. This will be the function we use to gauge performance. - Line 3: Create a variable

numwhich is the number of times we’ll do concatenation. - Line 4: Create a variable

str_to_concatthat binds to a string that will be used for concatenation. - Line 6-9: Perform string concatenation using

+=fornumtimes. - Line 11-14: Perform string concatenation using

join()from a list containingnumstrings. - Line 15: To make it fairer, I’m computing

a=1fornumtimes as well since+=also needs to do the assignment operation along with+.

The results will be kept in plus_time and join_time. The numbers you’ll see are the number of seconds it takes to execute the first argument of the timeit function for number times. Here’s the result I got on my computer:

num = 1,000,000 | num = 5,000,000 | num = 1,000,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|

str_to_concat = “Hello!” | str_to_concat = “Hello!” | str_to_concat = “HelloWorld” | |

+ | 0.70742 seconds | 16.46969 seconds | 1.86302 seconds |

join() | 0.01517 seconds | 0.07570 seconds | 0.01565 seconds |

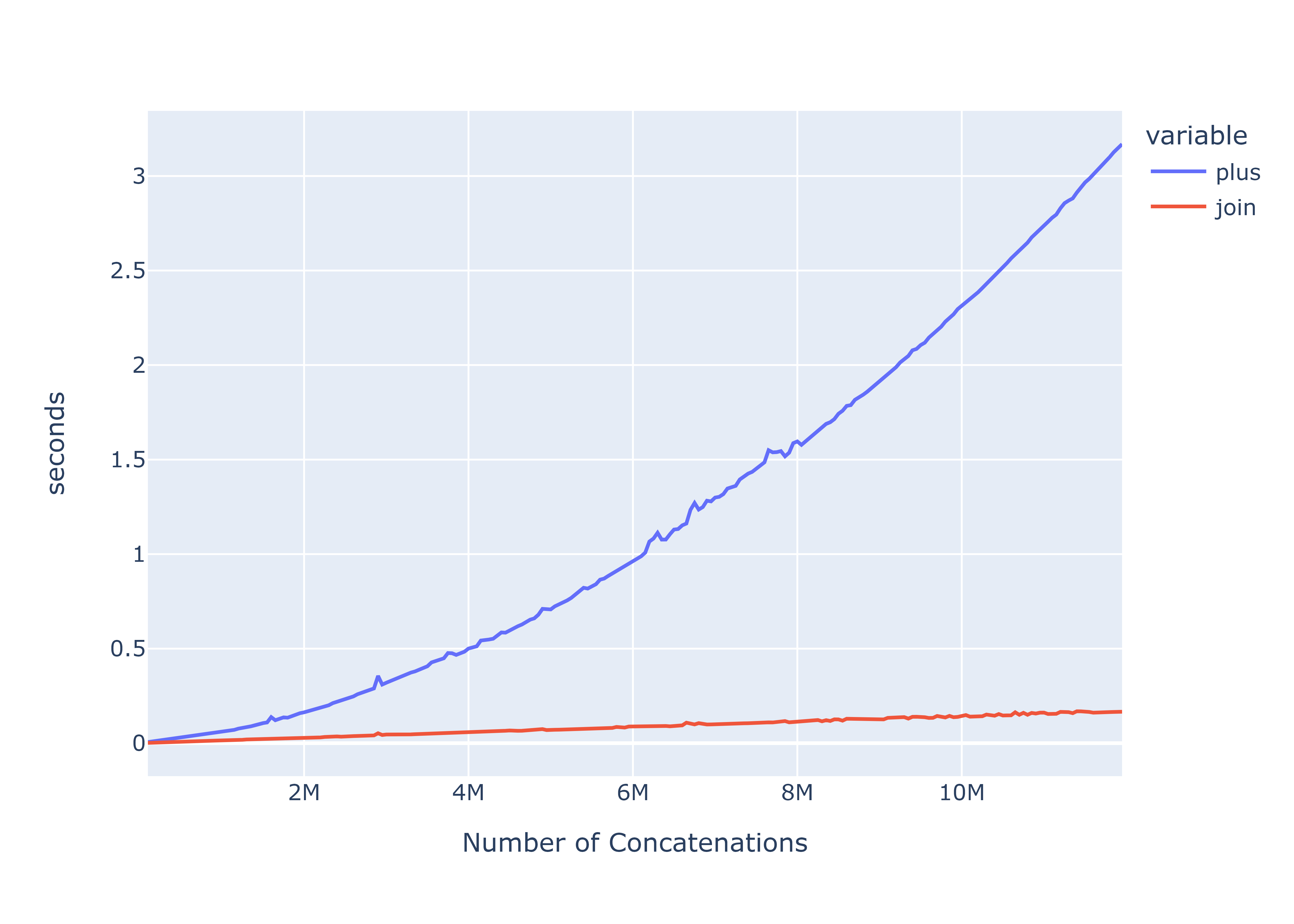

You are unlikely to get the same numbers, but the differences between join() and + should be very clear. join() is the clear winner here. But let’s take a closer look at the performance plot against the number of concatenations:

Comparison between join() and + when concatenating single-letter strings

Comparison between join() and + when concatenating single-letter strings

Now, it’s not quite simple to say that join() is $x$ times faster than +. They both have different growth rates. But to understand why join() is so fast, we need to understand why it’s so slow for the + operator first.

Redundancy Is Expensive

+ operator is a binary operator. What this means is that it takes only two arguments or operands as its inputs. When consecutive concatenations are performed like the following,

1

"I" + " love" + " Python."

what Python does is two separate concatenations from left to right. First is "I" + " love". The second is "I love" + " Python.". This impacts the performance for two reasons.

First, Python has to create two new strings; "I love" and "I love Python.". More generally, Python has to create $n - 1$ strings where $n$ is the number of strings you want to concatenate. Python’s string is immutable, so the value of a string cannot be changed. A concatenation between two strings will force Python to create a new one (or it could use an existing string if it has the same value as the resulting string).

This is a waste of resources considering the fact that we only need the last string. Allocating multiple objects by itself is not the main reason why concatenating with + is so slow though. Let’s take a look at this diagram:

The way + works can be roughly summarized as follow:

- Determine the size of the strings on both the left and the right.

- Create a new string with a size equal to the left and right strings combined.

- Loop through both strings and copy each character byte to the new string.

This is just for one + operation. So, in the diagram above, aside from creating a new string object, Python has to copy 6 characters in total to get the first concatenated string. Nothing’s wrong here. Next, we do another concatenation with the third string, copying a total of 14 characters.

You may have noticed that, for the second concatenation, we have to copy the string resulting from the first concatenation as well even though we have already done that the first time. Here, "I love" is copied twice. It may not look like much, but this redundancy compound the more strings you concatenate. This is the second and the primary reason why this method is so slow. To drive the point home, let’s take a look at a simplified version of this example.

In this example, I’m concatenating 5 strings, each with a single letter. The number in the diagram represents the number of characters that needs to be copied over to a new string. Notice how the number on the left operands increases every time a new string is created. After each concatenation, we are accumulating letters that need to be copied in the next iteration. In total, we need to copy 14 characters while it could have been 5. In a general case, for all the left operands, we need to copy

\[1 + 2 + ... + n-1 = \frac{n(n+1)}{2} - n = \frac{n(n-1)}{2}\]where $n$ is the number of concatenations. And for the right operands, we have

\[1 * (n-1) = n-1\]Assuming that we are concatenating only 1-letter strings, the number of characters we need to read and copy is

\[\frac{n(n-1)}{2} + (n-1) = \frac{(n^2 + n - 2)}{2}\]Notice that the largest term is $n^2$. As the number of contenations gets larger, this term will contribute the most to the overall performance. We called this quadratic time complexity as the work you need to do is proportional to the number of strings you concatenate raised to the power of a constant.

It will take longer to compute if longer strings are concatenated early.

Going Linear

The way join() works is very different from the + operator. It works like an n-ary operator. That is, it operates on any number of operands. The way join() concatenates strings can be roughly summarized as follow:

- Loop through the iterable in the

join()argument. - Determine the total size needed for the final string. If a separator is given, it will be taken into account too.

- Create a string large enough to contain all the strings and the separator.

- Loop once again to copy each character byte from each string to the resulting string. Insert the separator in between each string if given.

Notice that you only need to loop twice and create only one string. This means that there is no redundancy since each character in each string only needs to be copied once. For this reason, join() is able to achieve a linear time complexity - the work needed is proportional to only the number of concatenations. This would explain the graph we see at the beginning, but how is such implementation possible?

join() is actually not implemented using Python. It’s written in C and also a part of CPython which is the underlying implementation of Python itself, so join() is not constrained by things like Python binary operators. join() can directly interact with the mechanism used for creating string objects. Almost anything is possible in this realm! So, join() can specify the size of the string it needs without having to provide the value first and it can also modify the value in the string even though it’s supposed to be immutable. This is not possible within Python.

You can find the implementation of

join()in the CPython source code under thePyUnicode_Join()function inObjects/unicodeobject.c

Here’s a diagram representation of the same problem using join():

As you can see, it’s not that join() is fast. That’s just how an efficient algorithm should behave when performing multiple concatenations. The + operator is just not optimized to do this task.

Not All Characters Are Created Equal

If you play around with the example in the first section, you might stumble upon an interesting performance issue. If I were to concatenate strings with non-English characters. Let’s say, Thai characters. Here’s what I get:

num = 1,000,000 | num = 1,000,000 | |

|---|---|---|

str_to_concat = “Hello!” | str_to_concat = “สวัสดี” | |

+ | 0.70742 seconds | 2.68889 seconds |

join() | 0.01517 seconds | 0.01777 seconds |

In both cases, I concatenated strings the same number of times and both strings have the same number of characters. Concatenating Thai strings, however, takes longer to complete.

The reason for this is because Python uses Unicode code point to encode string’s characters. In Unicode, English characters were given the first 128 code points (U+0000 - U+007F) similar to ASCII. So, to store English strings, you only need 7 bits to represent each character ($2^7 = 128$). Thai characters, on the other hands, have its code points assigned from U+0E00 - U+0E7F. This means we need enough bits to represent 3 hexadecimal number. To represent a single hex number, you need 4 bits ($\log_2{16} = 4$), so you need at least 12 bits to represent a Thai character.

Each character in a Python string can occupied either 1 byte (8 bits), 2 bytes, or 4 bytes depending on the character with the largest code point in the string. If you have an English-only string, Python only needs 1 byte to store each character. (There is no support for 7-bit characters, so the best option for Python is to go with 1 byte.) If you have at least one Thai character in your string, the whole string needs 2 bytes per character. The number of bytes for storing string’s raw data is doubled compared to English-only string.

The storage size mentioned here does not include the overhead information of a string object.

In the previous example, concatenating “สวัสดี” which contains 6 Thai characters is equivalent to concatenating a 12-character English string. If you try this yourself, you will find the result to be very similar. Just for fun, you can also try with other Unicode characters like an emoji (U+1F600 - U+1F64F) that needs 4 bytes. Can you guess how long that would take?

Conclusion

By now, I hope that you understand that while it’s easier to concatenate strings together using the + operator, it’s not an efficient method to use with lots of strings. Under the hoods, Python is just repeatedly copying the same set of strings over and over again. It’s fine to do this on a small problem that doesn’t have that many strings to concatenate, but it’s better to resort to .join() when you start to see that performance dip! Hopefully, you find this article to be worth your while.